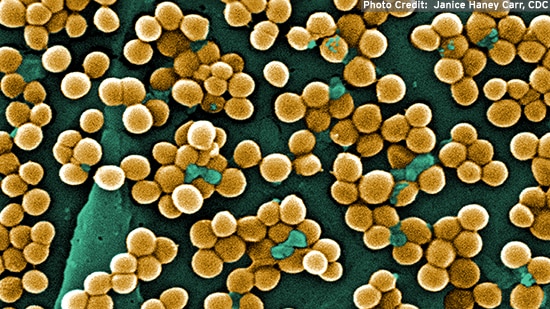

Staph. aureus MRSA

What is Staph. Aureus MRSA?

MRSA stands for Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It is a bacterium that has developed a resistance to most antibiotics such as Methicillin, commonly used for Staphylococcus infections. This results in infections that are more difficult to treat than ordinary Staph infections. While MRSA is no longer just a concern of hospitals and nursing homes, active surveillance done by the CDC¹ from July 2004 through December 2005 showed that the large majority of invasive MRSA infections were still healthcare-associated. This is further supported in an additional study by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, in which about 70 percent of the isolates were healthcare-associated.2

Healthcare-associated infections fall into two types: community-onset and hospital-onset. Clear understanding of the distinctions between these infections is important. See Table 1, which summarizes the distinctions between the different types of MRSA and their incidence.

Among the healthcare-associated infections detected by CDC, over two-thirds were community-onset and one-third, hospital-onset. Community-onset is defined as infections that occur in people with prior history of the presence of an invasive device at time of admission, history of MRSA infection or colonization, and hospitalization, surgery or long-term care residence in the 12 months preceding culture date. Hospital-onset is defined as cases with positive cultures isolated from hospitalized patients from a normally sterile body site obtained more than 48 hours after hospital admission. Incidence rates overall were highest among people age 65 and older.

Community-associated infections occur in cases without any of the documented community-onset healthcare risk factors noted above. CDC reported that 13.7 percent of infections in their study met the definition of “community-associated.” This is consistent with 2007 popular press reports of outbreaks of MRSA occurring in places such as schools, day care centers and camps.

Table 1. Distinctions between and incidence of healthcare-associated (HA) and community-associated (CA) MRSA infections, from CDC surveillance study¹

Healthcare-associate(HA) |

Onset designation |

Definition |

Percent of MRSA Infectionsa |

|

Community-onset

|

Infections that occur in people with prior history of the presence of an invasive device at time of admission; history of MRSA infection or colonization; and hospitalization, surgery or long-term care residence in the 12 months preceding culture date.

|

58.4

|

|

| Hospital-onset |

Cases with positive cultures isolated from hospitalized patients from a normally sterile body site obtained more than 48 hours after hospital admission

|

26.4

|

|

| Community- associated (CA) | Not specified | Infections that occur in the absence of any community-onset healthcare risk factors noted above. |

13.7

|

a1.3 percent could not be classified

Community-associated MRSA infections are genetically different from the hospital- or healthcare-associated MRSA, and some are severe enough to be fatal.3 Strains of MRSA that cause the community-associated infections have evolved to also become resistant to antibiotics commonly used to treat infections. In some cases, the infections they cause are potentially more virulent and result in different clinical syndromes than are typically seen with healthcare-associated MRSA. Additionally, a European paper suggests that to be defined as “community-associated” MRSA, such infections must be also biochemically confirmed to be MRSA and have an epidemiological background consistent with a community origin.4

Recent research has examined the role of domesticated animals with MRSA. A recent study by University of Iowa researchers confirms that swine may serve as a reservoir of MRSA and that transmission of MRSA occurs between swine and swine workers.5 A European Food Safety Authority report in 2009 confirmed that risk is higher among those in direct contact with animals, but also that contaminated food did not lead to an increased risk of MRSA.6

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS?

MRSA can affect people in two different ways – colonization or infection. When a person carries the organism, for example, on the skin or in the nose without showing signs or symptoms of infection, the person is said to be colonized. A recently published study estimated that about 32 percent of U.S. residents are colonized with Staph aureus, and about 0.8 percent with MRSA.7 If a person has overt signs of infection that are typically caused by MRSA (such as abscesses, wound infections, pneumonia, respiratory infections, blood, stool or urinary tract infections) the person is said to be infected.

Staph bacteria, including MRSA, can cause skin infections that may look like a pimple or boil and can be red, swollen and painful or have pus or other drainage. They are capable of burrowing deeper into the body, however, and causing more serious, potentially life-threatening infections, so they need medical attention. More serious complications include pneumonia, bloodstream infections or surgical wound infections. It is important to determine if an infection is caused by MRSA versus other Staph species to ensure proper treatment.

HOW IS IT TRANSMITTED?

Staphylococcus aureus is a relatively common bacterium found on skin and nasal surfaces of healthy people and animals. Therefore, it is not surprising that MRSA most often spreads from person-to-person by direct skin-to-skin contact or by surface-to-skin contact. It is possible for a colonized person to pass the bacteria to others through casual contact.

MRSA can also be spread by contact with the following surfaces: hands and skin, bar soap, towels, gym equipment, computer keyboards, lockers, door knobs and light switches.

HOW IS IT CONTROLLED?

Proper handwashing is the single most effective way to help prevent the spread of infection. It is important to wash with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer or by lathering hands with antimicrobial hand soap for at least 20 seconds and rinsing with warm running water.

Infection spread can also be prevented by covering any open skin (such as abrasions or cuts) with clean, dry bandages, avoiding sharing personal items (such as towels or razors), using a barrier (such as clothing or a towel) between skin and shared equipment, and wiping surfaces before and after use with an appropriate EPA-registered disinfectant with an MRSA claim.

Current infection control guidelines stress the need for meticulous cleaning.8 Recent studies support the recommendations for careful cleaning of environmental surfaces and disinfection of items. There is no convincing evidence that special cleaning agents are necessary. EPA does not recognize an efficacy difference between HA-MRSA or CA-MRSA and MRSA on disinfectant labels.

It is important to pay special attention to public areas and thoroughly clean them. These areas can easily spread MRSA. Use an EPA-registered disinfectant with a claim against MRSA. Carefully read and follow label directions for use and proper contact times. Consider cleaning and disinfecting “high-touch” hard surface areas on a more frequent basis. Also, perform training that reinforces cleaning and disinfecting procedures as well as all personal hygiene requirements, with special attention to hand hygiene.

Healthcare facilities are conducting surveillance activities to track and contain the presence of MRSA and outbreaks and to determine the effectiveness of control measures. This may explain some of the increases in reported incidence. However, although the overall percent of MRSA infections are continuing to increase, the CDC reported that the incidence of MRSA central line associated bloodstream infections declined by over 50 percent from 1997-20079. This indicates that some prevention strategies are successful and diligent attention to their implementation must continue.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION

1Klevens, R. M. et. al. 2007. Invasive Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298:1763-1771.

2Jarvis, W.R. et. al. 2007. National Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in inpatients at US health care facilities, 2006. Am J Infect Control 35:631-637.

3Shukla, S.J. 2005, Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Its Emerging Virulence. Clin Med Res. May; 3(2): 57–60. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1183432

4Millar, B.C. et. al. 2007. Proposed definitions of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). J. Hosp Infection 67:109-113.

5Smith T.C., et. al. 2009. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Strain ST398 Is Present in Midwestern U.S. Swine and Swine Workers. PLoS ONE 4(1): e4258.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004258.

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0004258

6http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/scdocs/doc/993.pdf

7Kuehnert MJ et al. 2006. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in the United States, 2001-2002. J. Infect. Dis. 193(2):172-179.

8Muto, C.A. 2003. SHEA Guideline for Preventing Nosocomial Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant Strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 24(5):362-386.

9Burton, D.C. et. al. 2009. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections in US Intensive Care Units, 1997-2007. JAMA 301(7):727-736.